Understanding Elections user journeys: lessons from in-person mobile testing

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, user research in government has largely shifted online. This transition has brought notable benefits, in convenience and flexibility, but it has significantly changed the nature of our interactions.

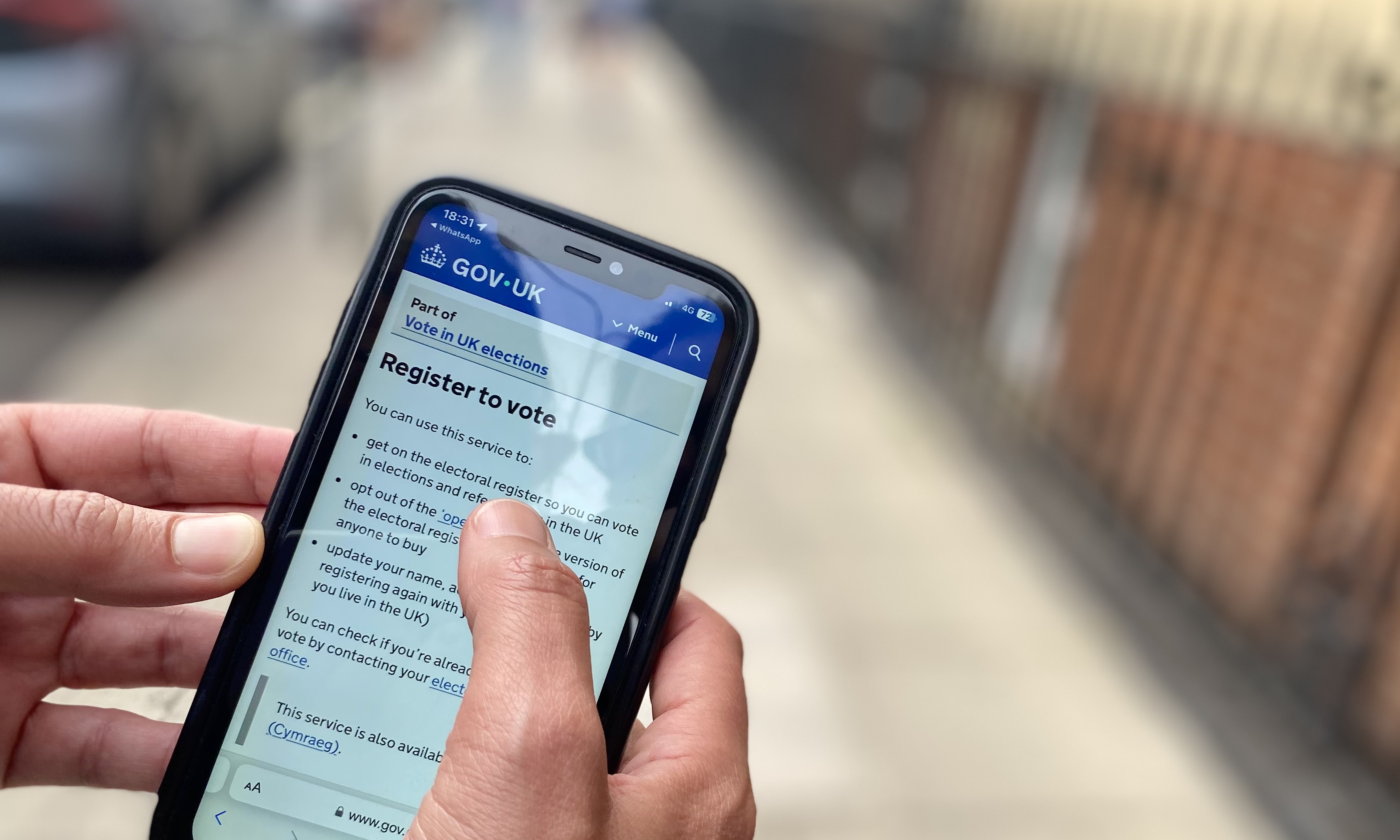

For our team within Elections Digital, working on initiatives to Improve Voter Registration, the virtual constraints pose specific challenges. Our goal is to assist the estimated 7-8 million UK citizens incorrectly registered to vote, or not registered at all, by making the process simple and accessible. In future, they may be invited to register through email and text prompts. Our statistics show that over 80% of current users of the GOV.UK Register to Vote service do so on a mobile device. Yet our early usability testing was only conducted remotely, on desktops.

We realised that laptop testing restricted our understanding of the mobile-first experience of many citizens interacting with government services. Formatting, accessibility, and interaction patterns are missed when viewed through desktop screen sharing. We agreed it was essential to undertake a round of mobile testing for the project.

The team initially considered remote mobile testing, where participants shared their phone screens via Microsoft Teams (MS Teams), but we discovered multiple issues:

Privacy risks: Participants might accidentally reveal personal content. Technical barriers: Screen sharing is inconsistent across devices and the MS Teams app is restricted on some company phones. Loss of facial cues: MS Teams doesn’t support simultaneous screen and camera sharing, so we can’t read participants’ expressions – valuable context that can complement or even contradict what they say.We considered workarounds like tech checks and creating a guide to screen sharing, but ultimately decided the complexity outweighed the benefits. That left the option of in-person testing.

Planning our first in-person usability testing

This was the first time anyone in the Elections Directorate had proposed in-person usability testing, and it came with its own risks around logistics, liability, and our duty of care to participants.

We explored hiring a usability lab – to access features like eye-tracking and one-way mirrors – but ultimately opted for MHCLG meeting rooms in Birmingham, which were free and adaptable to our needs. We worked with an external recruiter to enlist participants based on Electoral Commission research into groups least likely to be registered to vote. Recruitment was challenging due to our criteria and a tight two-week timeline. We scheduled six back-to-back sessions on a single day, with alternating facilitators.

Our designers created prototypes of the communications we would show participants, and the service itself, so they could move through with minimal facilitator interference. We created a discussion guide with mobile-specific prompts and contingency plans for technical issues.

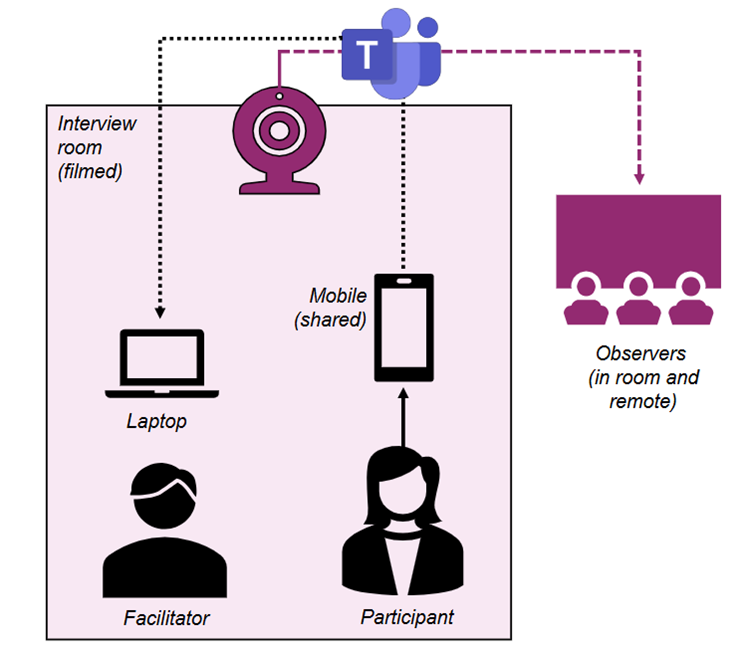

To reduce technical issues on the day, we decided to use a single personal phone with a proven ability to share to MS Teams. This allowed us to record sessions and let remote observers watch in real time. We used virtual observer rooms during each test to allow colleagues across the directorate to observe sessions in real time without disrupting the participant (see diagram below).

Each session involved two separate MS Teams meetings: one for the facilitator and participant, and another for observers. A separate, remote facilitator managed both calls, sharing the live session into the observer room while ensuring observers remained muted and off-camera to minimise distractions.

Overview of the set up for the in-person usability testing sessions.

Overview of the set up for the in-person usability testing sessions.

What happened on testing day

On 3rd July, we arrived in Birmingham armed with phones, chargers, extension cables, and printed materials, ready for all eventualities. We also pre-downloaded the testing materials to laptops in case of Wi-Fi issues.

Despite a few hiccups with recruitment (always be prepared for late dropouts!) the day ran smoothly. Each session followed a carefully choreographed routine:

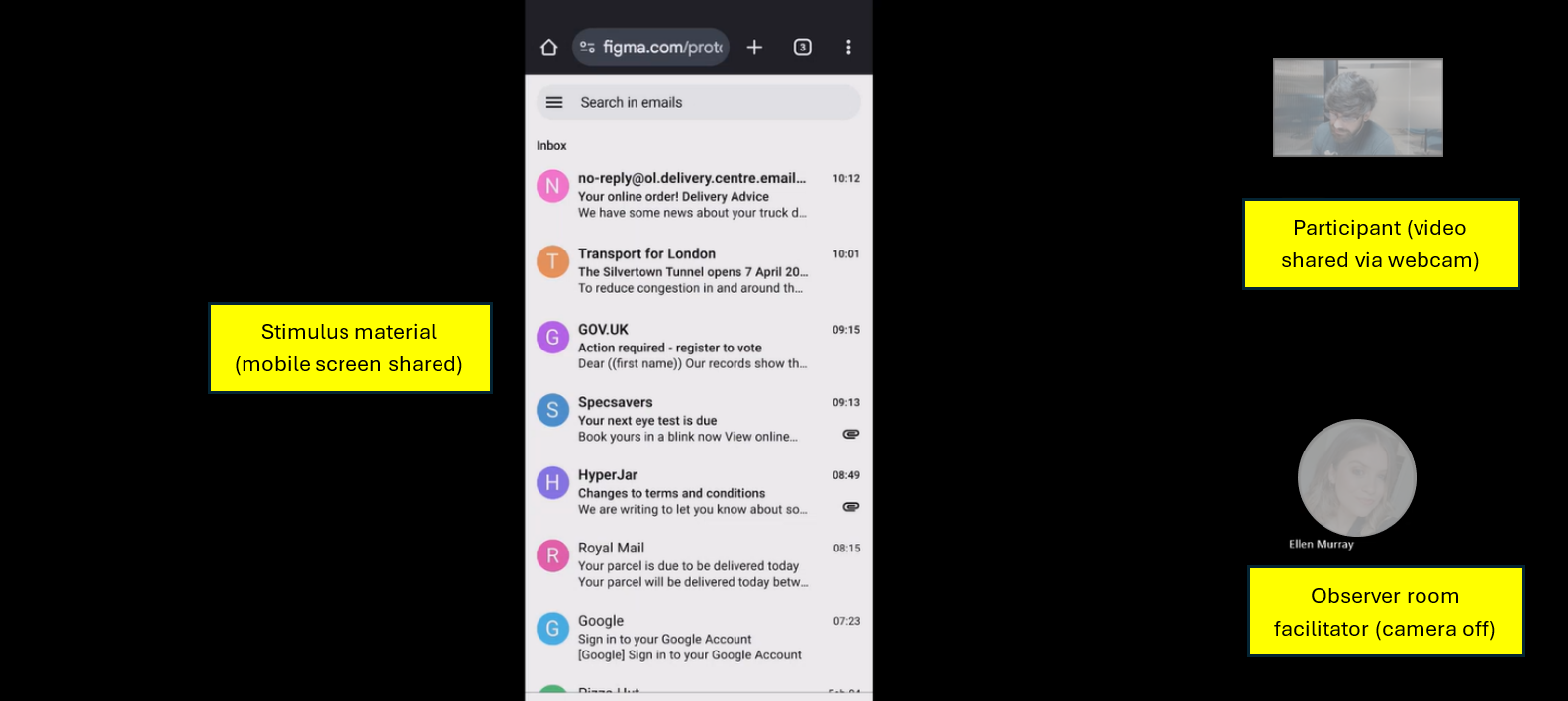

Participants checked in and were briefed by the facilitator. The phone screen and participant video were shared to observers via MS Teams (see image below). Observers watched remotely and submitted questions via chat. After each session, we reviewed feedback collaboratively and completed an assumptions table – a tool used to capture what we believe to be true about users, their needs and the problem space. Phones were wiped down between sessions. View of the session from the remote observers’ perspective on MS Teams.

View of the session from the remote observers’ perspective on MS Teams.

What we learned

In-person testing offered unique insights into how participants interact with services on mobile:

Readability and cognitive load: Due to the small screen size, mobile content is compressed, making it harder to scan and absorb. Participants often skimmed information on screens saturated with text. “Banner blindness” was more pronounced: some scrolled past GOV.UK headers or overlooked top-page content. Micro behaviours: We could observe scrolling, hesitation, and physical reactions in real time. Social cues: Sometimes participants’ behaviour contradicted their words, suggesting social desirability bias: pressure to provide positive feedback in an unfamiliar, “official” setting.This round of in-person mobile testing reminded us of the value of experimentation and adaptability in user research. Given that most users register to vote on mobile, it felt essential to test the service in that format.

In-person testing isn’t a cure-all. It brings logistical complexity and introduces potential biases. Participants may feel compelled to say the ‘right’ thing to please the interviewer. While we managed to organise this round in 4 weeks, the effort may be too intensive for larger or more geographically diverse studies.

Similarly, virtual observer rooms offer clear benefits – such as wider engagement, inclusivity, and learning – but they require additional planning, effort, and dedicated facilitation. It’s important to factor in the extra coordination and people needed to run them effectively.

Still, mobile testing of government services is critical to meeting users where they are. Our experience showed the value of reincorporating in-person methods for this testing, alongside the virtual norm. We strongly encourage other researchers to consider how they might once again meet users face-to-face to build more effective services.

Follow the progress the Elections Digital team on the MHCLG Digital blog.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments